This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity. See the full interview below.

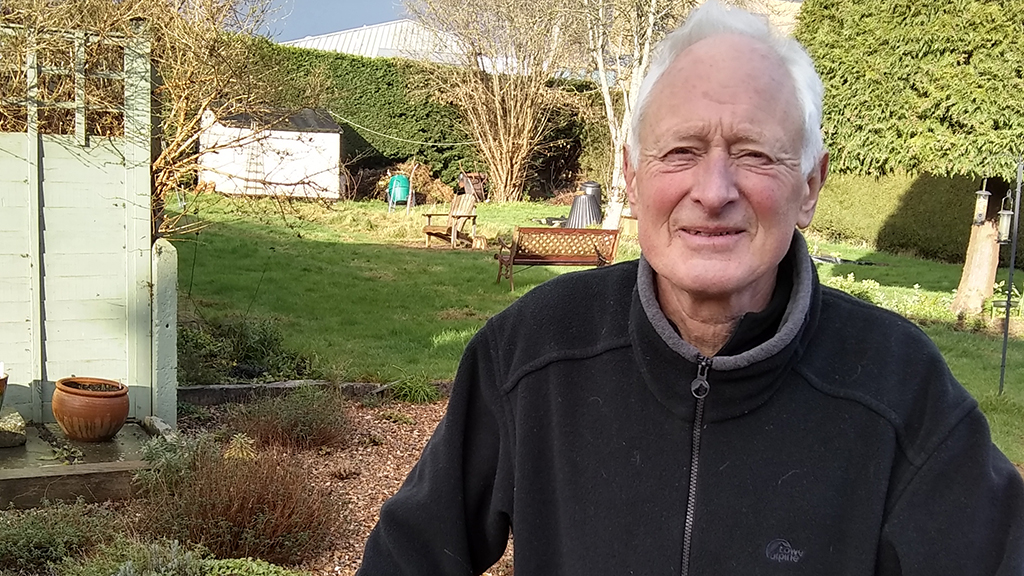

Mike Ginger has had a long standing commitment to sustainable travel issues, clean energy and energy conservation, growing food and lower impact consumption. He finds it regretful that the media and political process has been so slow to recognise deep environmental problems associated with obsession with conventional definitions of economic growth. Mike has worked on a series of sustainable travel projects including early cycle planning, infrastructure implementation and promotion/engagement in Bristol UK. He retrofitted his own terrace house with solid wall insulation, etc. to improve its environmental performance. Mike is currently retired and using his time as cycle campaigner, and is a founder of the Taunton Area Cycling Campaign. He is a proud steward of two allotments and an active member of Taunton Transition Town. He is a lover of taking bike rides in the wonderful Somerset countryside.

This interview was recorded on January 29, 2020.

Resources:

Centre for Alternative Technology: https://www.cat.org.uk/

Taunton Area Cycling Campaign: https://thetacc.org.uk/

University of Minnesota study: https://usa.streetsblog.org/2019/08/01/study-drivers-behave-more-dangerously-around-women-cyclists/

Transition Movement: https://transitionnetwork.org/

Incredible Edible: https://www.transitiontowntotnes.org/incredible-edible/

Rob Hopkins: https://transitionnetwork.org/people/rob_hopkins/

Our Planet by David Attenborough: https://www.ourplanet.com/en/

Fiona Martin (FM): Welcome Mike. Welcome to The Eco-Interviews. How are you doing this evening?

Mike Ginger (MG): Very well. Thank you. Yeah, had a good day out walking on the Quantock Hills in Somerset, so yeah, had a lovely day. Thank you.

FM: Wonderful. Well we’re excited to have MG with us. I’m going to introduce you briefly for our audience and then we will start our interview. So MG has had a long standing commitment to sustainable travel issues, clean energy and energy conservation, growing food and lower impact consumption. He finds it regretful that the media and political process has been slow to recognize deep environmental problems associated with obsession with conventional definitions of economic growth. Mike has worked on a series of sustainable travel projects including early cycle planning, infrastructure implementation, and promotion and engagement in Bristol, UK. Mike is currently retired and using his time as a cycle campaigner and is a founder of the Taunton Area Cycling Campaign. He’s a proud steward of two allotments and an active member of Taunton Transition Town. So Mike, tell us a little bit more about your involvement in the environmentalist movement.

MG: When I read that question, “how did you get involved in the environmental movement?” I’ve never really thought of it in those terms. I think there were just certain things that seemed wrong and you could see mistakes being made and they needed some sort of response. And I suppose I just got involved almost from an individual kind of motivation and seeing things happen that I just felt were very damaging and wasteful, and harmful to both people and the environment. So, that’s kind of how I got involved. And that was going back to school days, really seeing road schemes being built in the town I grew up in and businesses being destroyed and people’s houses being destroyed and that kind of thing. And communities being displaced, attractive streets being lost and sort of feeling that actually this is not really the right direction to be going in, particularly in urban areas. So that’s kind of how I think my awareness started. Then got involved in lots of different things.

FM: So this obviously goes back quite a few decades for you, like you said, as a child, what I understand is it started with the building up around your towns, the degradation of nature around you.

MG: Yeah. Not only nature but also the urban form as well. The urban structure and the pattern of living that used to exist, that was kind of swept away really by big road schemes. Yeah. When I was doing … so this is the top end of school, about 18 when this was going on. Yeah.

FM: And you said you took some individual measures. Do you want to talk a little bit about some of the stuff you’ve done? I know that you have retrofitted your house and you’re taking care of two allotments. Do you want to tell us a little bit more about that?

MG: Yeah, in the UK there are lots of terrace houses have single wall, what was called solid walls, so they haven’t got cavity walls. They’re very inefficient houses. So the house we lived in in Bristol, there was an opportunity to sort of get involved in a scheme to put what’s called solid wall insulation, which immensely reduces the loss of energy from inside or heat from inside the house going outside. So we did quite a comprehensive sort of scheme of having that done. We did windows, made those super efficient as well, all those kind of complementary sort of measures.

So that was just something that we’re able to do on a personal, individual level … Sorry. Yes, solar panels, I’m being prompted here. Yeah. Put solar panels on, things like that. Yeah, I mean in terms of food growing, for a couple of years, we lived in the Northeast of England and we moved down to Bristol and the gardens are really, really small. So I just thought it’d be nice to get what we call allotments, do you know about allotments? Do you have that sort of phrase? In America?

FM: We do in urban areas. I don’t live in an urban area, but they’re becoming, urban gardens are becoming more common.

MG: So these are individual plots, lots of them together in a site, and you’re responsible for just your own plot within that big site. And it was at a time when there’d been a big push on allotments as part of the war effort actually. And then they’d sort of largely fallen out of use in the 1960s and 70s and 80s, so it was in the late-80s that we, or I said, well, it’d be good sort of start growing some food of our own. So for a while we had an allotment on the side where there was hardly anybody else at all, really. People used to come down and burn furniture and things like that. But then there’s been a real resurgence in allotments in the UK and now there are waiting lists and even new sites being created.

So, we started off, I had not really done food growing before, started with one that went quite well. By the time we left Bristol we had three of these plots and we planted apple trees and things like that. So that was good. We had a neighbor as well who became a really good friend and so there was a lot of, literally cross fertilization of stuff going on there. So, that’s been really nice. And we moved to Taunton about four years ago and before moving, definitely needed to make sure we could get allotments here, which we have gotten a couple of allotments here on different sites. Yeah. So it’s just lovely being able to grow food more or less throughout the whole year actually. Do you grow food yourself?

FM: Yes. So my husband and I, we have just under an acre for our property and we have five raised beds in the back where it’s a little bit sunny and we have berries. And then we’ve just planted four fruit trees in the front of the yard. So we started with the backyard, which isn’t so much on the street, and now we’re going to go full hog on the front yard and it’s all going to be edible as much as possible. That’s where all the sun is. So yeah.

MG: That sounds good.

FM: So you mentioned something that’s interesting that I didn’t write out initially, but the popularity of allotments. So my father was a child during World War II in Glasgow, and so he went through rationing and, they were very inner city. They actually were separated from their parents and sent out to the country during the bombing. And so he experienced rationing and his father grew potatoes, I think. And you mentioned that they were popular during World War II. Even in the US they had victory gardens. And then after the war, as we started to prosper more, all of that learning and the interest in it was lost. But now we have this uptick in it, which I imagine is driven by the climate crisis. But how do you experience it as you’ve actually experienced it? Because, I wasn’t around during the war and I can only hear the stories and maybe you weren’t either, but my dad has mentioned it as a young child, the allotments and then they kind of disappeared.

MG: I wasn’t around when they went through that first phase, well I was around, but I wasn’t doing the allotments. So my involvement was really probably at the lowest point of allotments when people who’d had allotments during that period, they’d been dying off a lot of them. So all these allotments were becoming vacant, plots were becoming vacant and nobody was taking them up. So it was very difficult for them to get new tenants quite a long time. In the UK, we’ve had various sort of waves of green activism and even in the 70s.

We’ve got the Centre for Alternative Technology for example, in Wales, which is done a lot of development. That was established in the 1970s, so there’s been a certain level of consciousness I think the whole time, well since the 70s, and it’s kind of had the odd surge from time to time and people have gotten interested in doing practical things that are more kind of environment, lower impact, I suppose the production and the consumption process become closer, that you’re not removed from the actual production process.

So I think it was during that, I mean even in the 1980s there was a European election when the Green Party got 20% of the vote, which was previously unheard of, but then it fell back again. So climate was part of it, but I think just general being conscious of what was going on immediately around you and some people feeling a bit detached from where things were coming from, could they trust things that they were buying and eating, consuming. That’s sort of come and gone. In ways, it seems to have come back now probably more strongly than it’s ever been because of the climate crisis. But it’s been an undercurrent, I think they’re in society in the UK for sometime.

FM: That’s interesting. I appreciate hearing those stories, and the landscape I think is a little bit different in the UK. It’s a smaller country, fewer people, less land space, but a lot of people in a smaller land space. But I think there has been a little bit more consciousness because of the … from my experience has been in the news more, it’s more talked about, and it has been talked about in certain areas of the United States. Of course, California seems to be on the leading edge of that. But then there’s other areas of the US where I live in, the South, where it hasn’t really been talked about as much and now people are just starting to wake up to it. So it’s interesting to hear the differences and how it goes in waves through time periods.

MG: Yeah, I think it does. It’s very difficult to know what’s feeding what in terms of people’s heightened awareness. I think the media and the political process haven’t really until quite recently, have not really given that a fantastic amount of attention but then various things, individuals internationally pushed it all very much into the forefront of the media. And in turn it’s got higher up in the political process as well. And yeah, that sort of happened in the past to some extent, but it’s a much bigger surge this time.

FM: So speaking of the political awareness or urgency around environmentalism, the last interview I did was with a researcher in Australia and he talked about the detriment that the different Australian administrations have had where they had a lot of progressive climate policy in the early 2010s and then with the shift in the administration to Conservative, they wiped everything out. But he highlighted that, and I want to get your view on this as a UK citizen, that even throughout the turmoil of Brexit, that every party still seemed to have some sort of climate policy. Whether it’s enough, I don’t know, but is that a correct observation on his behalf? That even though, no matter what you think of Boris Johnson, there was still some sort of Tory climate policy in place? Is that correct?

MG: Oh yeah, it is correct. I think the last government, we just got a new Conservative government. The previous government, they did, I think they were the first European to go for carbon neutral by 2050. I think and we’ve obviously seen quite a big reduction in carbon consumption, which is mainly to do with our energy supply, coal being pretty much phased out and gas going down and a surprising increase in renewable energy. But having said that, people are sort of saying well to what extent is it because of government policy that’s happened almost in spite of government policy and there are some contradictory things that have been happening.

They were sort of opening up the possibility for fracking licenses. Just before the general election, they actually said, “no, we’re going to have a moratorium on fracking.” But that was just before the general election and I think there might’ve been some seats that could have been quite large or not where fracking was an issue locally. So, what level of long term commitment there is, remains to be seen. They also banned on-shore wind farms in the UK, which is actually the cheapest way of producing renewable energy.

Which I suppose has actually meant, there’s been quite a big focus on offshore and the costs of offshore have come down quite dramatically. With transport, which is the biggest issue, and talking about cycling advocacy and that sort of thing, there’s no real national funding going into cycling and walking. There’s no dedicated budget that local authorities can use to develop networks. But we have gotten very major road building program. So you’ve got those broad brush level, there just needs to be a strong commitment there. And I think that there are individual ministers and MPs who actually are quite committed.

Our own MP, she’s the Minister for Environment actually, she’s not the Secretary of State, but she’s senior within that sort of department. So she supports the Secretary of State and she’s been doing a lot of work around the new legislation that will come in when we leave the EU to try and maintain certain environmental standards that we’ve had under the EU. So there are some things going on which are positive, but there are some inconsistencies there and people are thinking can we just have more coherence and consistency and actually allocate the resources into the right areas to get real change, particularly in transport.

FM: It will be very interesting. It sounds like in some areas, the UK can be a positive example of taking the partisanship out of environmental policy, but you very much mentioned that there are some things that are not being addressed. So speaking about cycling and cycling advocacy, that’s a passion that you and I both share as cyclists. And I’m also advocating on the very local level here for cycling safety, cycling-pedestrian safety. So you’re one of the founders of the Taunton Area Cycling Campaign. Can you tell us about the cycling campaign?

MG: Yeah. Taunton is the sort of town that has fantastic potential for lots of walking and cycling. There’s lots of short car journeys, we do have about double the rates of cycling to work in the UK, I think it’s about 9-10%, and nationally it’s about 3-4%. So we’ve got quite a good base, but you can see there’s a lot of potential for more cycling. So I thought I’ll get involved in the local cycling advocacy or campaign groups we call it, and found that actually there had been groups in the past, but there was just nothing happening at the moment. So I actually organized a kind of online survey and we got about 300 people to fill in the survey and from that I organized a public meeting and formed the cycling campaign from that.

So that was about three years ago. I think we’ve started to have quite an impact. Yeah. So our approach is to say we want to work with the local authorities and support them and encourage them. But we also reserve the position of being a bit bolshy if we need to be, which we have had to do a few times. But it seems to work quite well. We seem to be able to maintain that sort of working relationship. But also, go to the media and do media events when we need to.

FM: Great. Three years in, that’s exciting. I’m only just less than a year into trying to organize our group. So I’m excited to not only share this interview with my sort of environmentally aware audience, but I want to also share this with the advocacy group I’m working on, to hold you up as an example and to share more about the Taunton Area Cycling Campaign. So can you describe the difficulties you have faced as a cyclist and then in a broader sense within the cycling campaign in and where you live?

MG: Well, as a cyclist individually, there’s sort of two aspects of that. I suppose one is just trying to get to travel around by bike. And the other aspect is sort of relationships in work context and social context. So traveling around, when we lived in Birmingham for a while, which is the second biggest city in the UK, and they had a major sort of urban road building program with these vast junctions, so if you wanted to cycle in from the suburbs into central Birmingham, you had to take on these massive free flow junctions. I mean I’m sure you’re very familiar with those sorts of layouts in the US because I think a lot of the design ideas came from the US.

FM: You’re welcome.

MG: So just feeling that it was just so unfair that these systems had been set up, which actually excluded lots of people who want to walk and cycle. And then obviously, traveling around sort of relationships with other road users as well. I tend to find that most drivers are actually okay, but there are some pretty aggressive drivers who do take ridiculous risks at our personal expense and safety. So there’s that aspect. And I started working in planning and transport planning when I first started working, and I was trying to get the people I was working with interested in doing more for cycling and walking. It was in the context of this city that had just built all these massive roads so there was a certain amount of hostility actually and almost ridicule back in those days.

That would have been the late 70s. So they’re the kind of issues I’ve had. But as time went on in terms of the working context of how more and more people were prepared to be won over really and would be quite supportive in their areas of work, trying to get things done. So I definitely saw that change happening from talking about cycling, walking, transport planning, working context, hostility, people not really taking it at all seriously, to people actually being quite happy to walk to work.

FM: And what message or group of messages did you find lessened the hostility? Or did it happen just with time? Something that I’m trying to advocate for, and similar to you, we’re trying to work with local authorities, with law enforcement and with County Council and these sorts of things. And there are so many ways to approach it. Like, I have a right to the road, I don’t deserve to die for walking or biking or, better transportation in all forms leads to economic growth because more people can get to work or, it’s better for the environment. Did you find something in your area that resonated with people more or less?

MG: I don’t think there was one single thing I think as you say you, you need to have the sort of range of arguments and you’ll find that in some context some arguments are more persuasive than other contexts. And sometimes it’s just down to individuals, isn’t it? Some people are just a bit more open minded and receptive and they see you as a human being and they respond in that way. Other people that are quite sort of stubborn and closed. So, I wouldn’t say it was necessarily a smooth thing and even now you get people to can be quite rigid and inflexible in their approach. But I mean all of those arguments that you’ve used, we’ve been doing some work with our police actually recently.

They’ve actually got quite a useful budget. We applied for some funding called the Road Safety Fund, and it’s based on fines that people have had for speeding or driving offenses. So they recycle this money back into community projects. You can apply for funding. So one of the issues in the UK is what we call the “Safe Pass” message. So that’s trying to get motorists to understand that they need to give you a wide space when they’re overtaking, recommended sort of 1.5 meters, although that’s obviously not possible on every road, but it’s a sort of general guideline. So we got some funding and we have some high visibility vests and backpack covers with a message on the back. And that’s gone down really well. So people have been wearing those and they’ve been finding it is making a difference.

It has the word ‘please’ in it as well. Somebody said the other day, “actually ,when you say please, it does make a big difference”, so stuff like that. The the police, you can report an accident, but now they’ve got sort of mechanism where you can report close misses and they say they’re gathering this sort of intelligence so that they can then focus their campaigns in the future. They can sort of target how they put their resources in the future. And they will accept camera footage and they do, they have done some follow up from camera footage, although there haven’t been any injuries as result, no incidents. So, but again with the police it really depends a lot on who you are dealing with. So we’ve dealt with some people who’ve been really good and other people who’ve been quite difficult. So two steps forward, one back, but it is two steps forward and only one back, so yeah.

FM: That’s great to hear that they’re recycling the funds that you were going to access so that’s certainly something. Finding funding has been difficult and it’s hard. We have a very disparate system of who do you go after? There’s a lot of nonprofits out there and so you can apply for a million different grants and we’re getting there. The thing I find about cycling advocacy is when you speak to people about it, there’s no one who will say to your face that you deserve to be run over because you’re on a bike or on foot. The law enforcement has been good since we’ve been able to get in touch with them. It took a long time to make a connection, and local government. And similarly my husband and I ride with cameras on our bikes cause we have the close pass issue and now our Sheriff’s Department has something in place for us to send footage to and they have knocked on at least one person’s door that I know of and told them don’t do that.

So it’s encouraging, and so I’m encouraged to hear about the campaigns that you are doing. So how do you see cycling and cycling infrastructure changing our current transportation landscape? What would you love to see in an ideal world when it comes to multimodal transportation?

MG: That’s a very big area to talk about. I mean what we’re saying is we, we’ve got this “Turn the Network Blue” campaign, I don’t know if you’ve seen on our website. Basically we’ve looked at all the places we want to join up locally and we’ve done a very broad brush policy the assessment of the links between those two places. I mean in some cases it might be two links, and we’ve sort of graded it. So blue is where there’s a reasonable connection that you’d feel fairly safe on. Red is where most people wouldn’t attempt to cycle because it’d be so difficult unless you’re very, very confident. So our campaign is “Turn the Network Blue”. But what we’re trying to lobby the local authorities to do is to go from what’s called a major scheme bid or a scheme bid central government, which prioritizes walk and cycling.

In the past they’ve always gone for road type schemes. And actually we’re quite pleased because they just about put a bid in for some funding. So funding bid to central government, which is focused entirely on a core part of this Turn the Network Blue network. So I think that’s sort of coming. I mean it’s not just us, they’ve declared emergencies and they’ve got public health issues they’re trying to address as well. And I think we’ve sort of helped push it along. So they are now seriously looking at how they can access funds externally to improve the network locally. We’ve got two tiers. We’ve got highway authorities in the upper tier, and then we’ve got the planning authority in the lower tier. And again we’re working with them quite a bit because there’s quite a lot they can do and they’re securing funds through the planning process that they’re going to be putting into walking and cycling infrastructure as well.

So slowly we’re starting to get to a point where money is being earmarked, being sought through bids, which can come to a reasonable sum. We’ve been working on a thing called a Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan LCWIP for short, it’s a real mouthful. And our group did about 25 route audits during the summer, which are fed into this plan which the Highway Authority have submitted to the government. So we’re hoping this may well come from that as well. So what we’re sort of saying is Turn the Network Blue, that will give you a kind of core network of routes. And then within the urban areas, all housing to be within 400 meters of that network. That network could be achieved through a number of means. Looking at the Dutch model, for example, it’s always on main roads.

You do need segregation on higher speed main roads, but on lower speed roads and residential areas, you can close roads off and create gaps or spikes for some. That can form very good routes and encourage cycling because the driving alternative has become longer. So it will be a mixture of measures, I think, from that point of view. It’s a question of how bold, ambitious the local authorities will be when it comes to actually doing the detailed design. One of the big issues for us is the detailed design of the cycling infrastructure as well.

We have a certain amount of cycling infrastructure in Taunton, but it’s not very well designed. So every time you get to a junction or a side road, you have to more or less give way. Whereas if you’re on the road, you just keep going, don’t you? Cyclists don’t want to keep losing momentum and having a conflict point every few hundred meters. So we’re doing a lot of work and again, thinking in the UK is moving in the right direction now to have much better standards for designing cycling infrastructure. So what it would look like I suppose would be something like the Dutch style of infrastructure on the ground and treatments of junctions.

We think probably we can at least double, maybe triple. So from the 9% journey to work, if that’s to say get it up to 25% that would have a major impact on transport conditions, environmental quality, public realm, the economy, as you say, more people having access. We’ve got quite a weak public transport system. So, no buses in the evening or on Sunday or very few on Sunday. So for people who don’t have access to a car, it’s quite limited. If you could ride a bike, you certainly can get to far more things. And obviously eBikes are quite a significant part of the picture as well because we’ve got quite a big rural hinterland with quite sizable settlements. But they’re 5-10 miles from the center of Taunton, which for many people, even with good cycling infrastructure, would be quite a bit of an ask to do those sorts of journeys.

But with eBikes certainly becomes quite possible. So there’s quite a lot of things coming together I think, which could be possible. What we really need though is for our government have an allocated national budget, so that the local authorities can plan ahead with certainty that resources will be available, rather than having to go for these one off bids every five minutes. We call them beauty contests, because that’s what they are. All these local authorities competing with each other and it takes up a lot of their resource and sometimes they don’t even get any money out of it. It’s not a good way to do longterm planning. Hopefully that’s covered the question in a roundabout way.

FM: Yeah. It excites me to hear the progress you guys have made and then the issues you’re facing. Where I live specifically, we have very similar issues except we have even less infrastructure, transportation-wise. Our entire country was built around the car. And where I live specifically is completely car centric. We don’t have any public transportation, there are no buses. And we don’t even have sidewalks in my town, so you’ll see people walking through the grass to get to their job and then if there’s someone with disabilities, that’s even worse. And if you’re an older person and you are unable to drive, you are basically relegated to your house or the care home, which is really sad and like you said, the multimodal aspect and having a bike and having eBikes.

I don’t ride an eBike myself, but I can certainly see the benefits. My husband and I were in Switzerland this summer and you know, there are hills everywhere. Not just in the Alps but absolutely everywhere. And we were huffing up this really steep hill in the town we were staying in and this older woman went zipping us on the eBike and I was like, Oh, but you know, she was doing her shopping in a very a fantastic way to get out and no need to take the car for those short journeys. Whereas where I live right now, if you want to go, I think the food store is three miles away from me, you have to take the car. I have run there before, but it is taking your life in your hands, which is not a pleasant experience. I think we have the same issues.

Like you said, if there is a centralized fund or a directive coming from the centralized government that disperses it out instead of exactly what you mentioned. For us it’s like applying for grants and it takes a lot of time and then the funds can be quite small as well. So what can you do with $10,000 or $75,000? Now I wouldn’t turn down any of that money of course, but when it comes to making significant changes and that longterm planning that’s needed, it has to be taken into account from the beginning of road planning and road restoration projects and $10,000 isn’t going to do that. I can’t do anything with that, you know?

MG: Yeah, definitely no. Another thing we’ve been trying to do, and it’s a bit of a stop gap before we get all the infrastructure, is one-to-one confidence sessions with people. We’ve managed to access, again very small amounts of money, a thousand pounds here, 500 there, but we’ve got a thing called Bikeability in the UK, I don’t know if you heard about this. But basically there’s three stages and this is a nationally recognized standard for training people up to certain standards in terms of their cycling competence and skills. So you start off with one, which is the primary school kids and that’s just in the playground. But level three is aimed at giving confidence and skills to people who can go out and cycle on the road system, and be a bit more confident into dealing with junctions and traffic. So we’ve been doing a bit of that and the uptake has been 100% for women, which is interesting. Yeah.

FM: That’s really, that is interesting.

MG: We’ve only done about 40 people, but it’s 40 people that are now cycling that wouldn’t have been doing before.

FM: Yes. That’s actually something that I want to approach our County Council about, is that the amount of people that say to me, “I would like to ride on the roads, but I’m just too scared.” Because many times it’s women, I mean there’s men as well. I know plenty of male road cyclists who say I only ride a mountain bike now because I won’t go on the road. But especially women and they completely have a right to be scared, just from anecdotal experiences. I feel like I get buzzed more than my husband does because maybe I’m not so much of a physical threat.

And there was actually a study done at the University of Minnesota and, I believe it was last year, that had male and female cyclists going out and recording incidents and the women did experience more incidents, unfortunately. But I’m all about getting women back out on the road. I mean the bike had a huge part in the feminist movement back in the early 20th century. It gave women who had no means of getting around to get out on their bike. And so that excites me as well, as a feminist.

MG: Yeah. What you are doing is that, I mean sometimes we think, there are a lot of barriers to overcome to make progress, but your context is actually so much more difficult than ours. I mean, you’re living in an area that’s not even got what we call footways or sidewalks but, same thing. Yeah. I mean that it’s just so basic. Here, within the urban areas and even sometimes between settlements, there will be narrow strips that people can walk along. They’re not particularly pleasant to walk along, but they do exist.

FM: Yeah, but we just got to keep at it. Well, what’s interesting for my locality specifically is that they did invest in a Bicycle, Pedestrian and Greenway Plan. They spent a lot of money to have people come out and make suggestions and it’s a huge, 168 page document that I’ve read. It’s exciting, the plans, but what’s disappointing is that it was published in April 2013 and as you know, we’re currently in 2020 and nothing has happened. So I feel like at least in my locality, that there’s a lot of lip service. If people get like, “why aren’t you looking at this?” And they throw us a bone and then nobody holds them accountable to follow through. We have a one mile bike lane in the next town over, that was painted in 2012 but it’s only like three feet wide. So you’re in the gutter and they don’t repaint it and they don’t clean it. So it’s effectively unusable.

And I’ve told local government that it would be better just to not have that bike lane because drivers assume that you have to be in it and if you’re not they get angry. So it’s an uphill battle but I think cyclists of the world unite and we’ll keep encouraging each other and I would certainly want to continue following the Taunton Area Cycling Campaign and stealing ideas from you guys that we can hopefully implement over here. And also get the excitement level up a little bit more because it can be tough, I think, with some of the people who are in my group, and myself, to keep the energy going when it’s so far uphill. But, we’ll get it done.

MG: Do you have any kind of regular meetings with the highways people? Do You have any kind of regular meetings with them where you can discuss things, maybe get things on board?

FM: So it’s very hard to speak to anyone at what’s called SCDOT, South Carolina Department of Transportation. I have some personal connections that advocate on our behalf so I’m happy for that. But what SCDOT has done, it has pushed it back down to the local governments, which is why I’m trying to get in front of the County Council. They say that they they need to hear from local government in order to do anything. So we’ll work on it. We’ll keep going.

MG: Yeah. There’s always that passing back sort of thing.

FM: Yup. I’m like “give me a name and I’ll speak to everyone and then you won’t be able to pass the buck anymore.” Because I have spoken to everyone and it will happen. Something else that was mentioned in your bio is the Taunton Transition Town. I’ve heard of this before but I don’t actually know what the Taunton Transition Town is. Do you mind telling us about that?

MG: Well it was something that was born out of what’s called the Transition Movement. Do

you know about the Transition Movement?

FM: Give us a history of it because I don’t know enough about it.

MG: My history is a bit vague because I only really got involved in the last two or three years, but it all started probably about nearly 10 years ago. And at the time it was to do with climate, but it was also based on what was thought at the time to be peak oil, although that’s kind of passed a little bit as a sort of pressing sort of threat. And the Transition Town Movement was to encourage and enable sort of groups in towns around the country to set up their own kind of practical grassroots project based groups.

So you’d actually do projects locally. So it could be around promoting cycling, but a lot of it was focused on food. So we’ve had this thing called Incredible Edible. So the idea is having bits of land in urban areas that don’t get used for anything and it’s kind of guerrilla gardening, really taking them over and planting vegetables, partly just for people to sort of see where vegetables come from, but also small quantities of herbs and things like that that people take.

So Taunton Transition Town kind of was established as part of that kind of wave of the Transition Movement, right at the beginning and there were some very dynamic people involved in setting it up at the time and they had all sorts of projects going on. They were doing street by street projects where you were kind of trying to work with other neighbors to work out how you could reduce your energy impact and reduce your transport network, those sorts of things. One-to-one advice and conversation.

And actually when I first came to Taunton, I went to the first meeting and there were about to wind up the group actually. Once you’ve got structure for a group you don’t really want to throw it away because new people might come in. And so in the end it was decided to keep it going for another year and then more people did start to get involved. I think most of the work we’re doing at the moment, we’re trying to set up a thing called a Repair Cafe. We’ve got a date to start that in April. So the idea is that people would bring in their broken things and get them fixed by knowledgeable people who can do that sort of thing. So it will be doing things like electronic stuff and computers and fabrics, that kind of thing.

And there’s been a growing project as well, growing vegetables in quite a nice location next to the river, and some events, we’ve run film shows, some of the current environmental films that have been coming out. And we had a big event in the town center called Going Green. So the whole range of activities there, people could drop in and get advice and information, there was music going on and refreshments. A range of things. Some groups have done a lot, lot more actually in they’ve become sort of little incorporated companies and their own rights and manage quite a lot of money.

There’s a guy called Bob Hopkins, he’s really thought to the founder, Rob Hopkins, Rob Hopkins. He’s a founder of the Transition Movement. So it’s worth looking him up online, actually. He’s based in a town called Totnes in Devon, which is sort of seen as being one of the centers of the Transition Town Movement. Yes, the Taunton Transition Town is just one of hundreds of towns have set up these groups.

FM: That sounds exciting.

MG: Yeah, it’s good stuff.

FM: The Repair Cafes is exciting. I’ve heard of movements or like in your neighborhood you can have a shared tools receptacle, I guess, and those sort of community based grassroots cooperative activities are super exciting. I can’t say that we’re there yet in our neighborhood, but we did have an environmental win in the town next door. They just banned single use plastic bags for the whole town. And so that’s a movement that’s happening in the US, ban single use plastic and the straws. And while it’s not going to save the planet, it’s getting people to think a little bit differently because they are forced to not use the single use plastic. Do you guys have that movement happening so much?

MG: Yeah, I think there’s been in the last couple of years. Did you see the Blue Planet series at all?

FM: Yes.

MG: Yeah, I mean that’s raised the consciousness dramatically around plastics and actually there was a very strong focus on plastics and reuse things and reuse plastics. And it was almost being too much of a focus and people weren’t looking at the other issues. But in terms of mobilizing, I think people sort of think these things, don’t they, they think ,”Oh that is not good we’ve got in these plastics.” Because they need something to articulate it and almost get a mass voice. And that happened I think with Blue Planet and David Attenborough. Yeah, so it’s very, very strong. And even when they, I think it was probably about three years ago, the government said you will charge for carrier bags in supermarkets. And some people were really grumbly about that, but just in the past now and everybody’s just used to it and it’s all very straight forward.

FM: Yeah. We’re four weeks into our plastic bag ban. So we still have a little bit of grumbling here and there in the parking lot about having to pay for a paper bag. I’ve been bringing my own bags for a while now. And you’re right, we get stuck in our ways. There’s a lot of stuff going on. We don’t want to make changes. But once you do make the small changes, it gets easier and then you realize, there weren’t these plastic bags 50 years ago and somehow everyone was just fine, and we didn’t have all these plastic bottles, but we somehow did okay. And that’s where it’s interesting.

Speaking to my father about when he was a child during World War II and he was like, “we used to have to take all the glass to the store.” And I’m like, “yes, that’s what we need to get back to.” But his generation saw the single use is such a relief that they didn’t have to do that. So I find my father and his wife, they’re in their mid eighties, they’re extremely reluctant to this change. But I have to just help them out. I got them some bags and stuff. They were so stressed about it. It’s okay. We’ll get through it.

MG: Let’s see. Oh yeah. Well I suppose people probably sort of relate that kind of behavior to quite frugal, difficult times, don’t they?

FM: Exactly, yeah. Single use was like this luxury, especially my dad very much watched the American movies back then and wanted to move and live in America, which is hence why I live in America. But that sort of disposable culture was seen as such a luxury. And so it’s interesting the different perceptions and how that affects people’s actions and what they think is okay. It’s funny, actually, when my husband and I started composting four years ago, I said to my dad, “we used to have three bags of rubbish go out every week and now we only have one bag.” And he was like, “Oh, do you save money? Is that why you do it?” And I’m like, “no, it’s because it doesn’t go to the landfill.” But you know, he doesn’t think beyond that. So, it’s funny.

MG: Yeah, yeah. I mean my dad’s in his nineties and I remember when I was a kid, we used to go to the corner off license where you go and buy beer and things like that and fizzy drinks. And I remember we was taking the bottles back and the guy who ran the shop saying, “actually in a few weeks time you won’t be doing this any longer because it’s going to be disposable from now.” And I do remember my dad and I talked about this and both the sort of saying, “well that’s a bit stupid, isn’t it really? Because that’s going to create so much waste.” And these kind of little conversations when you were younger and they sort of stay with you really, just little events do stay with you.

FM: Yeah, exactly. That being able to dispose of it was a luxury is similar. I actually, I lived in Venezuela for a year in 2006 and similarly if you buy beer, you buy it in a crate in the glass bottle and you keep the glass bottle and you take it back and it’s not due to environmental reasons. It’s due to just the lack of glass. So it goes back to the beer company and it’s washed and it’s reused. And so it’s not an environmental initiative, but you know that being able to drink a beer and throw the glass out is seen as something fancy. Whereas I would love to… We keep our glass, like I have all this glass, I don’t know what to do with it. We’re trying to figure out what to do with it.

MG: You don’t have a recycling system?

FM: Not where I live, unfortunately.

MG: Yeah. We have had recycling, think basic things like glass and paper for quite a long time. And now that we’re moving into much bigger range of materials are being recycled, so UK has not been too bad about that. Yeah. The recycling of food waste is, and they convert that into compost that can be used. We compost most of our food, I don’t eat meat, my wife eats a bit of meat-

FM: Same here.

MG: Yeah. So we don’t really, our food waste we can put it in the compost bins and it just produces all this fantastic stuff that you can use to feed the ground with, which is wonderful.

FM: I know, I really love composting.

MG: I see fantastic results, I see these tubs of great stuff look great. That’s the results, you know.

FM: I totally agree with you. Once you get into composting, there’s something very fulfilling about taking your waste and it becomes food for the food that you grow. And one of the funny things is, we always get volunteers out of a compost pile. And so, three years ago it was cherry tomatoes and last year it was butternut squash. And you know they’re just, we had like 30 butternut squash that came out of the compost heap from one grocery-bought butternut squash. The seeds were in there because I didn’t cook it, I’d done it raw. And it’s just very much the circle of life and it’s exciting that instead of something going to the landfill, you’re creating more and leaving it better than you found it.

MG: Yeah.

FM: Well I want to wrap it up with one final question for you, Mike. What advice would you give someone who has just woken up to the climate crisis?

MG: Well, don’t be demoralized by some of the more negative stuff you hear going on. Because I think as we’ve discussed us now, and if you sort of multiply that across the whole world, there’s a lot of positive activity going on and a lot of optimism in different areas. So I think we just need to think about bringing in that optimism and positivity together, don’t we? To try and counter some of the negative responses that you inevitably get. You know, if China doesn’t change or the US doesn’t change dramatically, it’s all for us in the UK, we’re 1% the CO2 emissions, what’s the point? But actually we’ve all got a contribution to make. Some of the changes are fairly easy to make. We’ve talked about transport, it’s obviously one of the most difficult ones. I mean the UK CO2 emissions on transport haven’t come down, they’re increasing.

So I think there are a few easy things and then perhaps try to think about transport, you know, walking and cycling more. It doesn’t have to be as difficult as you might think. I know it’s difficult in the US context because you’ve got just mainly roads that are very, very dangerous roads. In a UK context, often you can work out quieter routes, it might be a bit longer and you can get advice and support. There is a community around people that will give good advice and support on even things on sort of fixing your bike. You know there are projects that can help you get that done or enable you to get cheap bikes.

So, I suppose I’d sort of say, okay, do the plastics and do the recycling and grow a bit of food if you can and make sure you’ve got the right light bulbs and all that kind of thing. But sooner or later, start thinking about how you get around and benefit yourself by using active transport. You get the health benefits, you do your bit to reduce CO2 emissions and actually it can be quite enjoyable. Well it is. It’s very enjoyable too.

FM: Well, thank you Mike. I think you’ve highlighted some great grassroots organizing in Taunton with cycling and the Transition Town and what you’ve done as an individual and what we can all do as individuals to just take some action. I think individual responsibility, while the problem is quite large and a single person isn’t going to solve it, taking ownership of your individual actions empowers me at least to do more things that would help a wider group of people and at least organize people. And as you mentioned, talk to other people, get support and not be so singular on your own. It’s easier when there’s more people doing the same thing to get something done.

MG: Yeah. And you’re not alone. You are, as you say, part of a lot of people who want to see things improve. So just talk to people about it really, and work out who can give you support and who you can support. Yeah.

FM: Okay. Well, I appreciate it, Mike. Thank you so much for taking the time and chatting with us. I look forward to following this Taunton Cycling Campaign, and sharing this interview with people, and I wish you guys the best of luck. I do think I will be following you and getting ideas to hopefully improve what we’re facing where I live.

MG: Great. Well, yeah. Very good luck to you as well. I mean, before, I think you obviously facing some very … your context is very, very challenging. So it’s fantastic that you’re so enthusiastic and determined to having an impact, which I’m sure you will.

FM: Yeah. Okay. Well thank you Mike. Have a wonderful evening and we will be in touch. Thank you.

MG: Okay. All the best. Bye Fiona.